Balloon disimpaction of the fetal head at Caesarean birth

Was NICE fooled?

On 16 November 2022 the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) published IPG744, Advice on Balloon disimpaction of the baby’s head at emergency caesarean during the second stage of labour. The authors concluded (click here):

New evidence seen by NICE’s interventional procedures advisory committee showed the procedure was safe and effective to be used by maternity staff trained in managing impacted babies’ heads during an emergency caesarean birth.

For the full guidance and supporting documentation (click here).

Three randomised trials were considered. One is behind a paywall, and one in a hard to access journal, but I’ve uploaded pdfs.

Seal SL, Dey A, Barman SC et al. (2016) Randomized controlled trial of elevation of the fetal head with a fetal pillow during cesarean delivery at full cervical dilatation. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 133: 178–82 (click here, pdf here).

Sengupta M, Dutta S (2019) A comparative study of maternal and foetal outcome between reversed breech extraction technique and foetal pillow, during caesarean section in full dilatation (CSFD), in second stage of labour. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 8: 1463–68 (click here, pdf here).

Lassey SC, Little SE, Saadeh M et al. (2020) Cephalic elevation device for second-stage cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2020 135: 879–84 (click here, pdf here).

Seal et al. 2016 (click here, pdf here).

The Seal trial was the subject of an extensive critique by Andrew Grey on PubPeer in 2020 (click here). The trial was registered late and may have not had research ethics approval in one of the two recruiting centres. More importantly, an abstract reporting 202 participants was presented at the RCOG world congress in Liverpool on 24th to 26th June 2013 (click here). Although the trial recruited “between April 1, 2013, and March 31, 2014” the closing dates for abstract submission at that congress was 14 January 2013 (click here, screenshot here). i.e. 202 participants were recruited before the trial started!

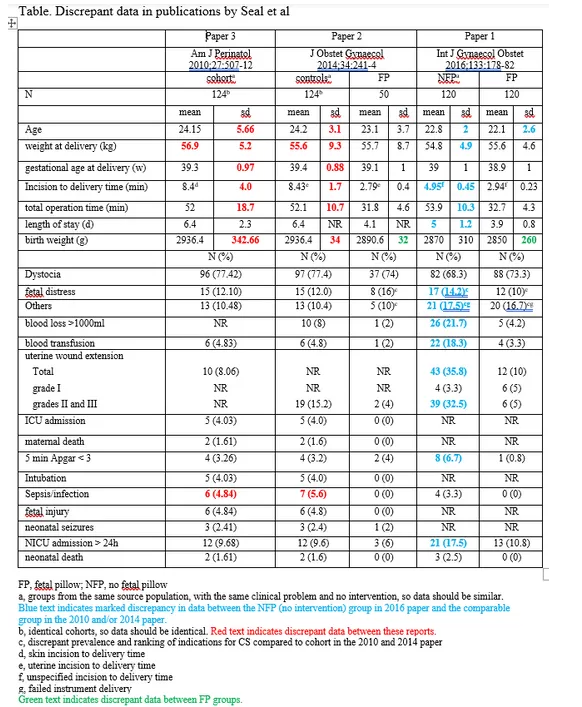

The same group of authors had previously reported a series of second stage Caesarean births (click here or pdf here) (Andrew Grey paper 3), and a non-randomised study of the fetal pillow with historical controls (click here or pdf here) (Andrew Grey paper 2). Although the series in Andrew Grey paper 2 and the historical controls were the same cohorts, there were a number of differences in the results tables. Grey also identified some significant differences between the control group (no fetal pillow) in the Seal RCT and the doubly reported historical control group from the same centres. See below for the table prepared by Grey

Inconsistency between the two cohorts does not, in itself, invalidate the trial, but some differences between the trial control group and the cohorts are hard to explain. For example mean operation times were almost identical (53.9 v 52 minutes) but incision to delivery time was almost halved in the trial control group (4.95 v 8.43 minutes). Rates of total uterine wound extension were fourfold higher in the trial controls 43 (35.8%) v 10 (8.06%) and severe extensions doubled 39 (32.5%) v 19 (15.2%).

Finally the trial was reported in three separate abstracts, at the RCOG British Congress in Liverpool 2013 as a poster (abstract mentioned above), and at the RCOG World Congress, 2015, 12–15 April, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (click here) as both a poster and oral abstract (click here). The three abstracts are reproduced below.

The recruitment periods and numbers reported in the three abstracts and the paper are summarised in the following table.

| Liverpool | Brisbane poster | Brisbane oral | Paper | |

| Recruitment period | 12 months | 14 months | 12 months | “Between April 1, 2013, and March 31, 2014” (12 months) |

| Nos. randomised | FP 100 No FBP 102 | FP 119 No FP 121 | FP 121 No FP 119 | FP 120 No FP 120 |

The shorter recruitment period and smaller numbers reported in the Liverpool abstract could be explained if recruitment was incomplete at that time, although there is no mention of an interim analysis. The differences in recruitment numbers in the two Brisbane abstracts and the paper, although small, are difficult to explain.

Andrew Grey’s Pub Peer post, which included other problematic issues, ended with: “These wide-ranging concerns raise very important doubts about the integrity of these 3 publications [the trial and two cohort studies], and the reliability of their findings. They could be addressed by independent scrutiny of the raw data, participant records, and ethics oversight documents.”

Dr Seal replied the same month, October 2020: “We have already responded to the journal editor about the queries. I will respond to your queries as soon as we receive answers from the editor. It may take some times. Thanks Dr subrata lall seal.”

As of November 2022, he has not responded further.

Immediately after Dr Seal’s response, the trial paper’s corresponding & senior author accused Grey and Pub Peer of libel in a long rant, ending with; “We are putting PubPeer on notice to withdraw their defamatory statements and publicise this to limit their libelous damages about our publications and devices.” Two further responses from that person were moderated by Pub Peer.

In summary, at best these data are unreliable and should not be used until the authors explain the inconsistencies and provide a full dataset. At worst the data are fabricated.

Sengupta & Dutta 2019 (click here, pdf here)

The Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences is not indexed on Pubmed but the article has a doi through which it can be found on Pub Peer.

NICE treated this as a randomised trial because the section “Data Collection Technique” reads as follows:

“The two techniques were applied simultaneously in the patients. The data was collected in pre-designed and pretested schedule. Randomization was computer generated. Treatment allocation was written on index cards and concealed in identical, sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes stored in the operating room. After creation of the randomization cards, the computer-generated randomization table was deleted.”

However, the following features suggest that it was probably not a randomised trial.

- The title does not mention randomisation

- The abstract does not mention randomisation. The abstract methods describe it as “a hospital based comparative prospective study”.

- In the main text the study is also described as “Hospital based comparative prospective study”.

- In main text the Sampling Technique is as follows: “Purposive sampling technique consisting of 25 patients in each group, i.e. 25 for Foetal Pillow and 25 for Reversed Breech Extraction Technique

- There is no Consort flow diagram.

- The control group were all delivered by reverse breech extraction, an unusual method for delivering a deeply engaged head, generally used after other methods have failed. This therefore points to purposive sampling of 25 patients delivered this way.

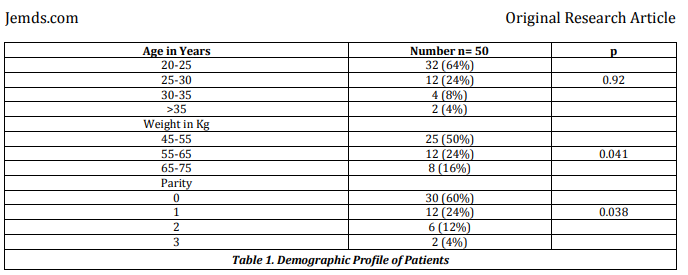

Even if the trial was randomised, the results are problematic. The baseline table, table 1, reproduced below, does not report demographic details by group, but inappropriately adds three P values in the right hand column. It is not clear to what these refer.

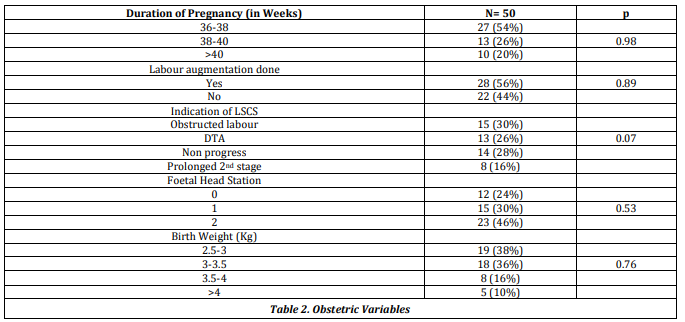

The same issue affects the obstetric variables, table 2, reproduced below.

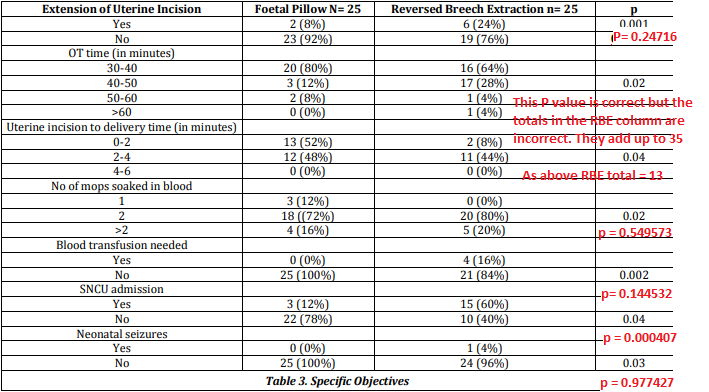

The results table, table 3, reports outcomes by group, but contains incorrect P values, and in two cases incorrect totals for the reverse breech extraction column, shown in red below.

In summary this trial was probably not randomised, and even if it was, the data are not reliable. It should not be relied on, unless the authors can provide an explanation and the original dataset.

Lassey et al. 2020 (click here, pdf here)

These authors report a single centre RCT conducted from January 2018 through July 2019 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. The trial was registered here on 17 November 2017. Planned sample size 200, achieved sample size 60. It’s understandable that trials sometimes don’t reach their target – money runs out, DMECs suspend it, triallists get exhausted – but it’s disappointing that the paper is written as if 60 was the planned sample size all along.

There are other inconsistencies in eligibility, and timing of consent and randomisation. Table below.

| Registry | Paper | |

| Planned sample size | 200 | 60 |

| Eligibility | “both nulliparous and multiparous women” | “Only nulliparous women were included.” |

| Consent | First stage, 2nd stage, or after failed instrumental. “Women will be enrolled from the labor floor during their labor course when there is concern for cesarean section for failure to progress in the second stage of labor. These women may be approached if they have a prolonged labor course (before they reach full dilation), when they get to full dilation and start pushing, or following an unsuccessful operative delivery.” | First stage only “All patients who met inclusion criteria were approached on the labor floor during the first stage of labor” |

| Randomisation | As soon as consent is obtained. “Once consent is obtained, the subjects will then be randomized 1:1 into two parallel groups, the Fetal Pillow Inflated (FPI) group and the Fetal Pillow Not Inflated (FPNI) group. A random number generator will allocate the groups in blocks of ten. | Group allocation revealed to the anaesthetist after the balloon had been inserted and the patient’s legs laid flat. “If cesarean delivery was to be performed in the second stage, women were then randomly allocated to either the cephalic elevation device inflated group or the not-inflated group. An independent consultant created a computer-generated randomization scheme that used balanced treatment allocation in blocks of 10, and the resulting sequential group allocations were kept in sealed, opaque envelopes until time of randomization. At the time of cesarean delivery, the cephalic elevation device was inserted vaginally by the obstetrician after catheterization of the bladder and after vaginal preparation with betadine, per our current labor and delivery guidelines. Once the cephalic elevation device was inserted, the patient’s legs were laid flat on the operating table in accordance with the guidelines for use of this device. The delivering provider and other members of the obstetric team were blinded to whether the device was inflated or not. Group allocation was revealed to the anesthesiologist, who inflated the cephalic elevation device using 180 mL normal saline (inflated group) or did not inflate the balloon (not-inflated group).” |

These ambiguities matter because the consort flow diagram is inadequate. It simply records that 60 eligible women were randomised into two equal groups of 30. There is no mention of compliance with treatment allocation, losses to follow up or any of the myriad of other problems one would expect to arise in a trial of this complexity, conducted during an emergency second stage Caesarean section. In two cases the Caesarean followed a failed instrumental delivery, and in 14 there was also a non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern.

To summarise, NICE has recommended that the fetal pillow is safe and effective, on the basis of one probably fabricated trial, one trial which was probably not randomised, and a third tiny trial, which failed to achieve its planned sample size and had a number of other worrying inconsistencies between registration and the final paper.

I’ve written to all three corresponding authors requesting trial source data.

Jim Thornton

Update. The Seal trial was retracted by Int J Gynecol Obstet in June 2023 (click here) and NICE reverted to its (2015) guidance the same month (click here). In brief, this describes the evidence as “inadequate in quantity and quality” and recommends use of the balloon only “with special arrangements for clinical governance and audit or research”. Good advice.

Absolutely brilliant investigation into “published” research. All the meets the eye is not always the truth or perceived to be.

Did you comment on the draft NICE guidance as part of the Avoiding Brain Injuries in Childbirth Collaboration?

No. As a private individual. What is ABIICC Jane?