Rich fools and their money

Sourdough Hotels

My Swedish house guest has just told me the craziest thing. There’s a place in Stockholm which, for a fee, will look after your yeast. A surdegshotel in Swedish.

You’ve heard of kennels and catteries, you’ve even heard of dog walkers and people to water your plants while you’re on holiday. But what about that yeast plant you’re feeding every day? Maybe for ginger beer, a Herman for cakes, or your favourite sourdough bread starter. Perhaps you even have a Kombucha culture. If you like home baking/brewing and long holidays perhaps this is for you. Click here.

But how did people manage before sourdough hotels? Even if they never went on holiday, they went to war, had bad days, or just forgot.

Their starters kept going. The best ones are based on wild yeasts and easily survive a few weeks of no feeding. If you pop them in the fridge, months. And if they die off, make another. The whole things a non problem. Another way to part rich fools from their money.

Go for it I say.

Jim Thornton

Stopping smoking in pregnancy

Nicotine patches don’t work

This is a piece of my own research – together with Tim Coleman, who led the whole thing, and many others. It’s a simple idea.

Nicotine patches, gum, sprays all help non-pregnant smokers quit. The effect is small but worth it, if it’s you.

But do they work in pregnancy? And are they safe? The answer should be yes to both. Even if nicotine harms babies, it’s probably less damaging than nicotine plus all the other crud in cigarette smoke.

But pregnant women metabolise nicotine quickly, so perhaps the normal dose is too low. And some may not really want to quit. We know that some actually want their babies to be small in the hope that they’ll give birth more easily! And many past treatments that were believed to be safe in pregnancy turned out to be anything but. Remember diethylstilboestrol, and thalidomide.

So it’s time for a randomised trial. Read the full report in today’s New England Journal of Medicine here.

Nicotine patches don’t work in pregnancy. For a couple of weeks women on the nicotine patches smoked a bit less, but by the end of the pregnancy smoking rates were the same in both groups. And there were no differences in baby outcomes either.

Oh well. Time to try something else. Maybe a higher dose.

Jim Thornton

You feel different when it’s your mum

The risks and benefits of HT*

An extraordinary article in this week’s BMJ trying to revive hormone therapy (HT) for post menopausal women. The authors suggest, among other nonsense, that HT reduces overall mortality.

Here’s the rapid response I sent in.

Is this article an advertisement? I note the authors all have links with the HT industry.

The claim of a dramatic reduction in hot flushes fails to mention symptom recurrence when the HT is stopped, and that the largest WHI (Women’s Health Initiative) trial showed no benefit on quality of life.

The graphs appear to have been derived from, and give equal weight to, the largest randomised trial (WHI) and the largest observational study, the Nurses Health Study. If the latter were removed and the other eight randomised trials included, the effect on all cause mortality would be in the opposite direction (odds ratio 1.06; 95% CI 0.94 -1.19) (Sanchez et al. 2005).

For the 51 year old woman with hot sweats, HT provides short term relief. It increases the chance of some diseases, namely cardiovascular disease, strokes and breast cancer and reduces that of others, including osteoporosis, bowel cancer. The exact risk-benefit ratio varies with the woman’s prior risk of each disease but the precision of the estimates is insufficient to allow individualised risk assessments.

When they learn that there is no overall improvement in quality of life, and that in the trials overall mortality was increased, most women wisely decide to live with their hot flushes.

Gabriel Sanchez R, Sanchez Gomez LM, Carmona L, Roqué i Figuls M, Bonfill Cosp X. Hormone replacement therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002229. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub2.

I also mentioned my own conflict of interest. Namely that my mother died of a stroke while taking HT six months before the Women’s Health Initiative trial was suspended because of the increased risk of stroke. But she was a good age and there’s only a small chance that the HT, which she was taking on my advice, killed her.

The important lesson to take from the observational Nurses Health Study, and the randomised WHI trial is to be sceptical of observational epidemiology.

Jim Thornton

*Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) changed to hormone therapy (HT) Jan 2016

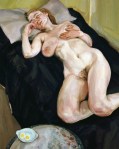

Painter and Model

Celia Paul

Celia Paul, Lucian Freud’s pupil, mistress, and model appears at least twice in the current exhibition of his paintings at the National Portrait Gallery. In Painter and Model from 1986-7 she is the artist – as in real life, but without a canvas and easel. The naked man uncomfortably stretches his foot towards the paint on the floor. He’s not enjoying her right foot pressing on a tube of green.

In Naked Girl with Egg 1980-1 she is in the traditional mistress’s pose – naked and exposed.

But fertile? The bisected boiled egg on the paint stained table isn’t. It’s breakfast.

Jim Thornton

Do fat people really want to lose weight?

Do smokers want to stop?

Proper economists, i.e. not the accountants who call themselves health economists, don’t set much store by what people say. They tell you what you want to hear, what makes them look good, or what gives them them the best chance of getting laid. If you want to know what people really want, look at their actions.

A fat person who claims to want to lose weight but then goes large on a Big Mac is not telling the truth. Smokers who claim to want to give up, obviously don’t. That’s why telling people to diet, or stop smoking is generally a dead loss. But doctors still have to get fat smokers out of the door. Here’s an idea.

There is a grain of truth in the claim that I really don’t want to do something that I carry on doing. The benefits of eating and smoking come now, while those of stopping are in the future. We prefer good things now.

A commitment contract brings forward the pain of not stopping. You agree to give up a sum of money large enough to hurt, and only get it back if you achieve your goal. It works. Proven by randomised trials (Volpp et al. 2008, John et al. 2011).

You can strengthen the effect by agreeing to give the money to your enemies if you fail, or dividing it among other contractors who succeed. Anyone can do it. The rich just need to put a larger sum at risk. There are websites to take care of the arrangements. e.g. StickK.com.

Go on. Join up.

Or else shut up. Obviously you don’t want to give up.

Jim Thornton

Volpp KG et. al. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 300: 2631-7.

John LK et al. Financial incentives for extended weight loss: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26: 621-6.

Abortion Ethics 6

The Golden Rule

Is there an alternative to fretting over women’s rights, and whether fetuses are people? The utilitarian philosopher Richard Hare believed so. He argued from the Golden Rule; “Treat others as you would wish to be treated in the same situation”.

Since most mothers would not have wanted to be aborted when they were fetuses, abortion is, on the face of it, wrong; even for a fetus with spina bifida who is likely to be handicapped, because if we were that fetus we would choose life in a wheelchair rather than no life at all.

But imagine that the mother plans a family of just one child. If she carries this pregnancy she will bear a child with spina bifida. If she aborts she can have a normal child who would not otherwise exist. That “replacement” child would wish the abortion to happen. The mother cannot act as both the spina bifida and the replacement child would wish.

Hare asks what you would choose if you had to live through the lives of both children? Reject abortion and get one life in a wheelchair and one non-life. Abort, and it’s one non-life and one replacement life in full health. You’d obviously choose the latter, so the mother should abort. Wow! Abortion in the interests of the child – the future child. But Hare has hardly started.

Consider how this type of argument plays out with the more usual types of abortion; those considered by young women not ready for a baby. They probably will have another child later. How much better will that later child’s life be? Will it be better or worse if the mother has the first abortion?

There are more people to consider than just this child now and possible replacement/future children. All children affect other people’s lives. Not just in big ways, by marrying them, or taking the job they wanted, but in all the minor ways in which each of us improves or harms the welfare of others.

Hare argues that if we consider how all these other people would view the abortion, the decision becomes rather like deciding whether to reproduce at all. The high likelihood that the present fetus will exist without abortion creates a presumption that abortion is usually wrong, but it’s hardly a knock down argument. In an overpopulated world, if the mother would struggle to look after the baby, if the present fetus will be handicapped, abortion might be the right choice.

Hare asks us to consider what abortions we would choose if we were as yet unconceived. i.e. from behind a veil of ignorance. If we did not know whether we would be conceived and live, conceived and aborted or be a replacement fetus after another abortion. We would know the chance of being a boy or girl, being handicapped, being unwanted, born to a single parent, living in an underpopulated or over crowded world. He thinks we might be fairly liberal.

Or perhaps it is too complicated to judge. Thinking about future people and replacement fetuses is tricky. One of Hare’s pupils, Derek Parfitt, wrote a whole book, Reasons and Persons, about it thirty years ago. It made my head ache.

But the complications are similar to those faced by people deciding whether to reproduce at all. We solve them by leaving the decision to parents. They, especially the mother, are probably best placed to act in their future children’s best interest.

This is my last post in this series on abortion. Let me summarise.

Fetuses do not have the characteristics of people in the sense of “beings who may not be unjustly killed”, so abortion should be permitted. Even if they were, forcing women give up their bodies for nine months to bear them contradicts our other intuitions about our own bodies. If neither of these arguments convinces you, try this. In the interests of the people who will one day come to exist some abortions are morally right. The best people to judge are parents.

Jim Thornton

RM Hare. Abortion and the Golden Rule. Philosophy and Public Affairs 4. No 3 Spring 1975.

Abortion Ethics 5

Women’s rights and famous violinists

Perhaps the whole debate about the status of the fetus is misguided. Perhaps abortion is permitted even if the fetus is as much a person as you and me. After all we don’t force women to give a kidney, or even a pint of blood to save an adult life. Why should we force them to carry a pregnancy? But perhaps that’s not a fair analogy.

The philosopher, Judith Jarvis Thomson, came up with a better one. Her thought experiment is an analogy with abortion for rape, but not limited to that.

A famous violinist, i. e. not just a person who valued his own life but someone whose life was also valued by many others, develops a fatal kidney disease, which can only be treated by connection to the circulation of another person for nine months. He has a rare blood group and it is difficult to find somone with the right group who is also willing to be connected. A Society of Music Lovers hear about the problem, search for a suitable person and find you. Rather than asking if you would agree to be connected, they kidnap you and connect you to the violinist’s circulation. The next day you wake up and the clinic director explains what has happened. You demand to be disconnected, but the director says his hands are tied. He can’t disconnect you without killing the violinist, an undisputed person with his own right not to be unjustly killed.

Should you stay connected? Obvously it would be kind of you to do so. But must you?

Judith Jarvis Thomson says that if after due consideration you decided that you couldn’t cope with nine months connection, you should be allowed to disconnect. If so we should also permit abortion for rape victims, whatever our belief about the personhood of the fetus.

OK you say. I’m convinced about abortion for rape, but what about abortion for a woman whose contraception has failed? Jarvis Thomson’s thought experiment can be adapted to that easily. Imagine it was well known that the Music Lovers were on the hunt for a suitable victim in your town. The police warned people to not travel home alone. And imagine that you decided to cross the local park to take the pleasure of exercise, or of viewing the sunset, and the Music Lovers jumped out of the bushes, abducted and connected you. Would it make any sense for the clinic director to say, “I would have disconnected you, but I can’t because you brought this on yourself by your feckless behaviour”? Surely not. By analogy taking sexual pleasure does not commit you to bearing the pregnancies that occasionally result, whatever the personhood of the fetus.

Next, a quite different way of looking at abortion.

Jim Thornton

Judith Jarvis Thomson: A Defense of Abortion Philosophy & Public Affairs, Vol. 1, no. 1 (Fall 1971). Available on the web here

Abortion Ethics 4

Religious arguments

Perhaps the previous posts made you cry out: “Wrong, just wrong! The fetus is special because it has a soul, given by God from the moment of conception.”

You’d be right. Maybe God revealed this truth directly. Maybe your parents taught you. Maybe you got it from the Bible, Koran or whatever book guides you. It doesn’t matter. For you, abortion is equivalent to murder.

But it is a religious belief. It has its sphere. No adult should impose their religious belief on another. You’d hate to have someone else’s belief imposed on you. So your belief that abortion is murder is an excellent reason for you to forego abortion. But it’s a bad reason to prohibit an unbeliever, or a believer in a different tradition, from choosing one.

That’s all on personhood – the fetus is not a person, but religious people often disagree.

In Abortion Ethics 5, we try to bypass the person thing. Is abortion justified, even if we’ve erred thus far, and the fetus is a paradigm person with all the privileges that go with that status?

Jim Thornton

Abortion Ethics 3

The problem of newborn babies.

In the previous post we argued that the fetus fails to fulfil the requirements of personhood because it is not a self-aware being that values its future life. We suggested that some higher animals, might approach our definition and should be treated carefully. We argued that this was a strength of our argument.

The problem is that this argument appears to commit us to permit infanticide. Newborn babies are not self-aware, and don’t, as far as we can tell, care about their future life. Can we also kill them if they are inconvenient?

The answer is yes, if no other person is prepared to make the effort to look after them. The value of newborn babies lies in the importance other people give them. They are precious in the way an inanimate, but otherwise important painting like the Mona Lisa is precious. It is not a person, but destroying it would be wrong. Killing a new born baby is not the same as killing a person, but so long as its mother, or the nurses looking after it, want it to live then it is still wrong.

Imagine if no-one cared enough to expend effort looking after a particular newborn baby. Perhaps its mother had other concerns, or it was so premature that the only nurses who could look after it, also had other concerns. Perhaps they needed time with their own families. This might happen as technology for saving the lives of premature babies grows more complex. At that point we would surely allow the last neonatal intensive care nurse to switch off the ventilator with a clear conscience.

Other societies, such as the Spartans, have permitted infanticide in the past, and some, India and China, tolerate it even today. They don’t regard newborns as precious in the same way we do in the West. They are different but not immoral.

To summarise. Neither the fetus nor newborn babies meet morally important criteria for beings who may not be unjustly killed. Their importance lies in how other people feel about them. Abortion is therefore permitted at the mother’s request because no-one else is able to look after her fetus. Infanticide is prohibited in modern western society because many people are willing to look after newborns and would be outraged by their killing. In other societies things might be different.

In tomorrow’s post we examine religious objections to these arguments.

Jim Thornton

Abortion Ethics 2

Is the fetus a person?

In the previous post we set out part of the pro-life case as follows:

Killing innocent people is wrong

The fetus is a person

Therefore abortion/killing the fetus is wrong.

In this post we examine the claim that The fetus is a person. First we need to define person. Let’s be circular, and define it as a “being who may not be unjustly killed”.

The obvious answer is humans, members of the species homo sapiens. On that definition the fetus is a person and, on the face of it, abortion is wrong.

But, although it makes intuitive sense, the homo sapiens claim does not bear close examination. It is speciesist, in the same sense as it would be racist to claim that only whites are persons. They are both distinctions based on morally irrelevant criteria, namely skin colour, or species membership. The reason we don’t immediately perceive the speciesist claim as such, is that on this planet the only undisputed contenders for personhood are members of the species, homo sapiens.

We need a thought experiment to clarify things. Here goes:

Imagine a spacecraft landed outside your house one day. How would you decide in what sense to have the occupants to dinner? Get it? Would you eat them, or sit down together and share a meal? Before you answer, remember they are making the same decision about you.

The answer is obvious. You would not decide on the basis of their species. You would assess their mental state. Are they conscious, self-aware, do they want to live, would they be deprived of anything by painlessly dying? If the answer is yes, you should not kill them, and if they’ve made the same judgment about you, they also should let you live.

So now we have our definition – consciousness, self awareness, wanting to live, stuff like that, are what makes people people. For now we need not go into the precise definition any further. We can already see that the fetus does not make the cut. Or if it does we are already being unfair to many other animals.

On this definition personhood/non-personhood is a continuum. Some higher animals, primates, dolphins and whales probably also fulfil some criteria for personhood. Maybe they are conscious, aware of themselves and grieve when their family members are killed. This is a strength of our definition; we should be careful how we treat such higher animals.

But however we look at it, the 12-week fetus is not even a borderline person on this definition, so abortion is permitted.

Not so fast! You can already see many obvious objections. In Abortion Ethics 3 we look at some of them.

Jim Thornton